Exercise programs commonly incorporate aerobic and strength training components. How far should an athlete be pushed when doing exercise in terms of intensity? Physical therapists who work with athletes aim to use optimal intensity for strength training. The purpose of this blog is to discuss evidence-based exercise prescription and offer a tool for improving precision in exercise recommendations. Exercise prescription incorporates volume, exercise density, and intensity. Volume includes the duration of the exercise as well as the dosing of sets and repetitions. Exercise density has been suggested by authors to compare the amount of work completed to the period of recovery.1 Ideally, this ratio can be self-regulated both subjectively and objectively.2 For example, an unconditioned patient may require several minutes of rest after performing lunges compared to a conditioned patient that only requires 30 seconds of rest between sets of exercises. The unconditioned patient subjectively may perceive their efforts to be an 8/10 difficulty and the conditioned patient may perceive the same activity as a 3/10. This perception of difficulty can also be compared to objective physiologic responses to exercise to provide a true measure of difficulty such as in heart rate measured before and after the exercise.

Physical therapists can assist athletes by dosing the volume, exercise density, and intensity of a training program. Clinicians frequently underdose patients in clinical practice.3 The pervasive use of 3 sets of 10 repetitions without modification lacks the necessary individualization of the exercise program and fails to optimize strengthening progression. Holten’s curve suggests finding a 1- repetition maximum (1RM) for an exercise for a healthy client.4 Using a percentage of the 1RM can be used for dosing exercise intensity. In 1945, DeLorme suggested 3 sets of 10 repetitions should be used, but it should also be noted that DeLorme qualified this by stating that progressive loading must occur to optimize gains in strength.4 For some reason, the second portion of DeLorme’s statement – progressive loading - has not been followed.

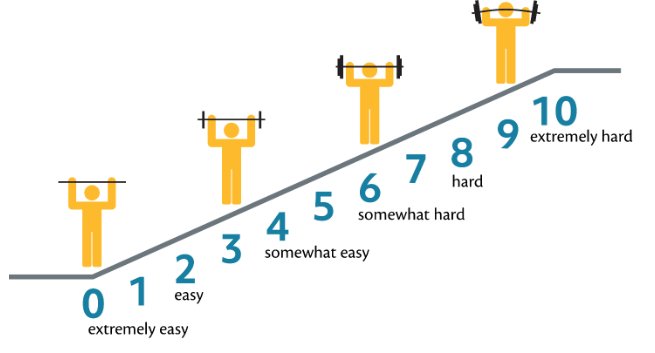

“One measure to consider for assessing intensity is the use of the OMNI-RES scale.6 This simple scale is ideal in determining how many repetitions the athlete has in reserve before exertion and if the load can be increased.”

Multiple variables can be manipulated to increase the intensity of an exercise program, among them, load, volume, and exercise order. Load is the amount of mass lifted, and volume is the total number of repetitions in a session multiplied by the resistance used.5 Changing the order of exercises within a session contributes to benefits for the athlete in breaking up the usual load pattern and adding variability.5 Progressive overload of the muscles can be achieved using many different approaches without defaulting to 3 sets of 10 repetitions. Options such as increasing the load or increasing the volume through increased repetitions, sets, or number of exercises performed or altering resting time between sets or increasing the repetition velocity during submaximal resistances are effective in increasing strength.5

Larsen et al2 suggest focusing on subjective self-regulated rates of perceived exertion and asking the athlete how many repetitions the athlete has left in reserve when performing resistance training. Specifically, the authors noted that this was an effective method for enhancing maximal strength measured by a 1RM when following a resistance-training protocol. Larsen et al2 suggest that gains or losses in strength may be due to daily fluctuations in fitness, fatigue, and readiness of the athlete to perform over time.

One measure to consider for assessing intensity is the use of the OMNI-RES scale.6 This simple scale is ideal in determining how many repetitions the athlete has in reserve before exertion and if the load can be increased. Included here is an edited version of the OMNI-RES that was first introduced by Lagally and Robertson.6

The OMNI-RES is used to determine when to increase exercise intensity in an athlete’s program. Optimal intensity is vital to enhancing performance. The OMNI-RES should be assessed at baseline when the athlete initially performs the exercise with resistance. Resistance could be in the form of weights, tubing, or bands. The athlete is asked to use the OMNI RES scale to rate the level of difficulty from 0-10 for the exercise.5 When the athlete is able to perform the exercise with 3 sets of 15 repetitions and reports an OMNI-RES score that falls below 5, resistance should be increased by one pound or one resistance level of the tubing or band. The athlete should be retested at that next level of resistance by reassessing where they would rank the intensity using the 0 -10 OMNI-RES scale.

I am not sure why the OMNI-RES is not more commonly used in the clinic. I don’t see clinicians using it, and I usually see clinicians relying on habit and clinical impression for the selection of level of resistance to use. Perhaps this happens to our students as well since they are following the typical clinician practices. I think we have to continue to strive for excellence in the care of our athletes. We need to reflect on how we dose exercise, what we say to our patients, and what message we are giving them. Why is it that asking a patient about their pain level has become commonplace but not quantifying the effort and intensity an athlete is exerting in an exercise? As an educator and a clinician, I need to use tools that have evidence to support them. The OMNI-RES has demonstrated construct validity with the Borg Rating of Perceived Exertion Scale and provides objectivity to a subjective measure of intensity.6,7 Yet, clinicians don’t use it.

As physical therapists, we can do a better job of dosing exercise to our patients with an athlete-specific intensity.

References

- Skorski S, Mujika I, Bosquet L, Meeusen R, Coutts AJ, Meyer T. The temporal relationship between exercise, recovery processes, and changes in performance. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2019;14(8):1015-1021. doi: 10.1123/ijspp.2018-0668.

- Larsen S, Kristiansen E, van den Tillaar R. Effects of subjective and objective autoregulation methods for intensity and volume on enhancing maximal strength during resistance-training interventions: a systematic review. PeerJ 2021; 12;9:e10663. doi: 10.7717/peerj.10663.

- Hoover DL, VanWye WR, Judge LW. Periodization and physical therapy: Bridging the gap between training and rehabilitation. Phys Ther Sport. 2016;18:1-20. doi: 10.1016/j.ptsp.2015.08.003.

- DeLorme TL. Restoration of muscle power by heavy resistance exercise. J Bone Joint Surg 1945;27:645-667

- Lorenz D, Reiman MP, Walker JC. Current concepts in periodization of strength and conditioning for the sports physical therapist. Sports Health. 2015;10(6):734-747. doi?

- Lagally KM, Robertson RJ. Construct validity of the OMNI Resistance exercise scale. J Strength Conditioning Res 2006;20(2):252-256. doi?

- Bautista IJ, Chirosa IJ, Tamayo IM, Gonzalez A, Robinson JE, Chirosa LJ, Robertson RJ. Predicting power output of upper body using the OMNI-RES scale. J Human Kinetics 2014;44:161-169.

Author Bio:

John Heick, PT, PhD, DPT is a tenured Professor at Northern Arizona University in Flagstaff, Arizona. John received the James A. Gould Excellence in Teaching Orthopaedics Physical Therapy Award in 2021. John received his clinical Doctorate and master’s degree in physical therapy from Shenandoah University. Dr. Heick received his PhD in 2015 from Rocky Mountain University of Health Professions in Orthopaedic and Sports Science and his dissertation was on concussion assessment. Prior to physical therapy education, John was a medic in the Air Force for 12 years in a primary care clinic and performed aero- medical evacuation in various aircraft. John has practiced physical therapy for 20 years in various settings including the emergency department, sports, orthopaedics, neurologic, wound care, aquatics, inpatient rehabilitation, acute care and in a balance center. John continues to practice clinically prn in an orthopaedic/sports outpatient clinic and in a pro bono Orthopaedic clinic. John is board certified by the American Board of Physical Therapy Specialties in orthopaedics, neurology, and sports.